A fresh start.

Endlessly Free is the first programme of NDT’s 20/21 season, the first under leadership of its newly appointed artistic director Emily Molnar, and marks the return to the stage of the company after lockdown. Seen live on Thursday 17 September in The Hague and via livestream in my dimly lit livingroom the day after, this article draws from the impressions of both experiences combined.

On Thursday, Molnar significantly introduced the programme focusing on the positive drawn from present circumstances, still felt in the tight protocol of access for (what felt like) the handful of people sitting in the enormous Zuiderstrandtheater. If anything, she mentioned, Covid-weirdness allowed them as a company to “reconnect with the value of intimacy and poetry that can be brought about by dance”.

Far from empty words, the three chosen pieces did just that. Turning context into what one can only hope is a curatorial statement for the long run, Molnar’s agenda behind the assembled programme was clear. Presenting The Other You (2010) by Crystal Pite, together with Soon (2017) and the premiere of Silent Tides, both by Medhi Walerski, Endlessly Free popped a threefold cork and rose to the occasion by bringing the party back to the basics. A sense of intimacy unites the three, yes, but also a focus on the best that NDT has brought to western dance tradition in its 60 years of history: a certain kind of dancer. Outstanding technical abilities (based on – but not restricted to – ballet) and a capacity to fully give in to movement, making it silently personal, turn the biggest assets of this world-leading company into nuclear, poetic bombshells – always on the verge of exploding.

With rehearsals starting when direct contact was not allowed, Silent Tides evolved as social distancing measures loosened. Aptly and vividly building on the hunger for touch, long time NDT-dancer Medhi Walerski premiered a masterful duet serving as a metaphor for the core aspect of existence we all missed throughout these months.

Upper body uncovered, their costumes a simple yet elegant pair of white trousers with matching white socks, Chloé Albaret (magnificent) and Scott Fowler introduce the piece with two solos, dressed in space only by a long horizontal line of fluorescent lights floating in the background. The musical score, designed by Adrien Cronet, loads the choreography with a nostalgic undertone while accentuating some of the movements with fitting, sound-effect-like accents. It makes complete sense, even more so when, as the dancers come closer to one another to finally connect through touch, Cronet’s final, long, electronic string note fades into Bach.

Eureka. What does Bach stand for, if not for the experience of beauty superseding craft? Reminiscent of both Hans van Manen and Jiří Kylián, Walersky focuses and builds the choreography on and around the vibe of the dancers. As they playfully move around, with and responding to one another, the cinematically fitting musical accompaniment and the bare, minimalist light design (shifting from that fluorescent light to a calm, all-engulfing and golden twilight) accentuate the precise, wave-like combinations while making the energetic link between the two dancers unmissable. It’s precisely that. What we missed, and what does the magic. Impossible to transmit over the screen, the livestream directed by Ennya Larmit provided a privileged and worthy substitute for it by drawing the dancers’ faces and their way of looking and searching for each other closer than ever.

Silent Tides. Photo: Rahi Rezvani

In Crystal Pite’s The Other You, starring Jon Bond and César Faria Fernandes, the added value of the livestream was felt the most. This theatrical dance duet, quintessentially Pite, portrays two dancers playing different characters of a single mind. One mirrors the other, then manipulates his body at a distance like a puppeteer. Intertwining several scenes with moments of darkness, it all happens in a semi-circle of black-cloaked chairs, with distant urban sounds in the background – now and then, a dog. A non-defined yet recognizable place: reality is close by, but not enough to feel comfortable.

Like in Silent Tides, here too a classical score – Beethoven’s Clair de Lune – is introduced to accompany the second part of the choreography, starting after a long and anguished scream by the manipulated Bond. After that, the tables in their relationship start to turn, leaving us to wonder who owns who, and putting the focus on a recognizable and unending, individual struggle. While in The Hague the precision with which both dancers executed Pite’s famous way of echoing and chaining movements together carried us through the piece from afar, the livestream allowed for a more immersive experience, making every twitch of a finger, every facial expression and every whisper theatrically readable, and the fantasy complete. (Note to self: a good set of headphones is a plus).

Soon | photo: Rahi Rezvani

Soon | photo: Rahi Rezvani

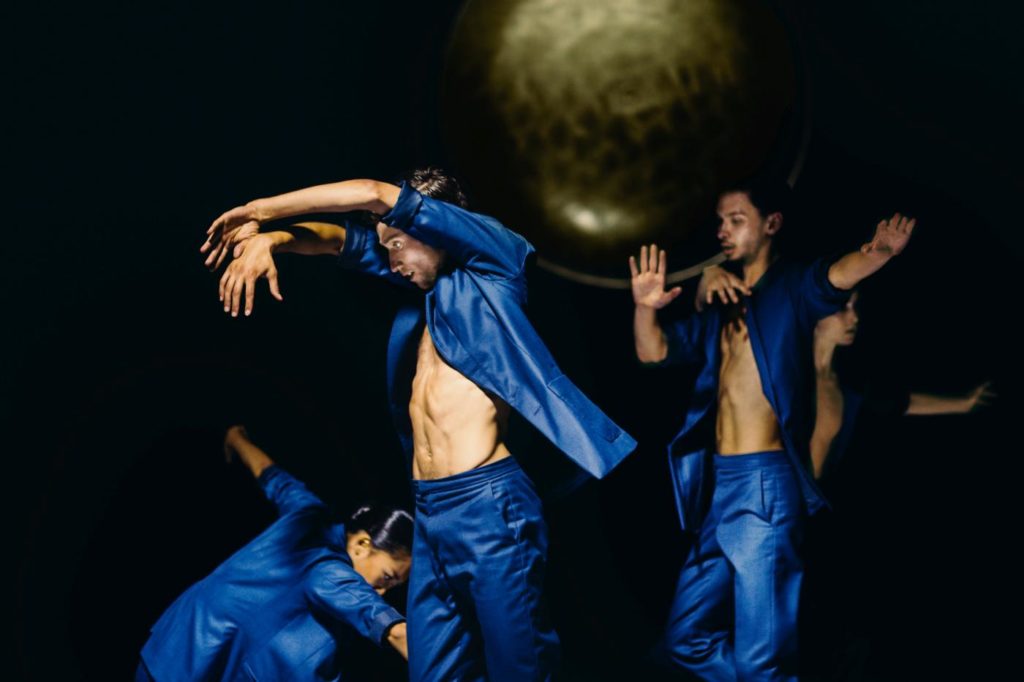

On the other hand, Walerski’s Soon reminded us of all that livestream life cannot match. Seen in the theatre, the magnificent visual installation – a giant pendulum balancing and slowly turning around in mid-air, centre stage, with a bright spotlight on one side and a huge, mottled golden half sphere on the other – encases the whole experience with a sense of quiet sophistication. The elegant contrast with the electric blue suits worn by the four dancers adds to the esthetic. On top of the impossibility to deliver this effect – lost with every switch to close-up – the swiftness with which the dancers move across the stage in this piece makes the uncanny gap between life and this form of technical reproduction painfully visible. Paraphrasing Walter Benjamin: the aura is lost.

Set to music by Benjamin Clementine, Walerski’s quartet best connects to the title of the program. Celemetine’s music is fluid, navigating shamelessly and with orgiastic beauty from jazz to classical to spoken word to…“Adios!”. With stark lyrics that talk about the dark sides of the world, his melodies carry an undertone of freedom, and of hope. Walerski honours the four chosen Clementine songs by not illustrating them. Instead, he parallels the music with an evenly elegant and imposing esthetical framework; and with choreographic choices that allow the dancers to outdo themselves. Witty and clean, the bodies are organised to forge unity at certain moments – hopping together for a few bars, or building up visual statues to have them swiftly dissolve a second later – while allowing each of them to fill in their part as free spirits within a whole.

In that joy, in that intimate and powerful and visible sense of being present, of letting go within control, the hope resounding in the songs is translated into movement. And the dancing bodies seem to be, just for a moment and despite everything else, endlessly free.

Welcome back. Hello Emily Molnar. And long may they reign.

Photos: Rahi Rezvani

Jordi Ribot Thunnissen. Originally published: September 21 2020. Movement Exposed